Between Roots and Rooftops

Banana Yoshimoto’s short essay, published in Japanstory.org, reminisces about the Tokyo neighborhood of Shimokitazawa and the loss over the years of many of its charms. “All relationships, not just our love affairs, prove awfully difficult once the brightest days are behind us” is how she sums up her growing disaffection with the place.

Yoshimoto writes that smaller, independent businesses used to be lifeblood of the city, keeping things interesting. She blames their disappearance on the neoliberal policies of the government of Junichiro Koizumi, who was prime minister from 2001 to 2006. Since then, she claims, the distinctive atmosphere of the neighborhood has disintegrated, its ragtag collection of local shops and places with tasty food giving way to shiny chain stores and restaurants.

Despite Banana Yoshimoto’s longing for a lost Shimokitazawa, it remains one of Tokyo’s more vibrant and promising neighborhoods, best known for its many vintage clothing stores among a maze of narrow streets. Notable among recent developments is the Shimokitazawa Bonus Track, a living-working environment, on top of land owned by Odayku, a private railway company.

The studio set out to build on this promise through architectural and urban interventions at a variety of scales, responding to neighborhood needs and broader demographic shifts—including the realities of degrowth—that are reshaping Japan. By combining adaptations of existing structures with new buildings and reimagined public spaces, we aimed to restore some of Yoshimoto’s faith in the city and its possibilities for conviviality. In this, we drew inspiration from Ivan Illich’s Tools for Conviviality, which celebrates “autonomous and creative” relationships between people and their environments.

Our work began with a trip to Shimokitazawa in Setagaya Ward, where we met the mayor, attended community consultations, and spoke with local developers. We also toured projects elsewhere in Tokyo and learned directly from Toyo Ito and his colleagues about their ongoing work.

These encounters informed students’ choices of sites and programs. Before traveling, we studied Shimokitazawa’s form using maps and aerial photographs. Each student designed a preliminary intervention around our action area near Shimokitazawa Station. This preparatory work helped guide site selection and project development once on the ground in Japan.

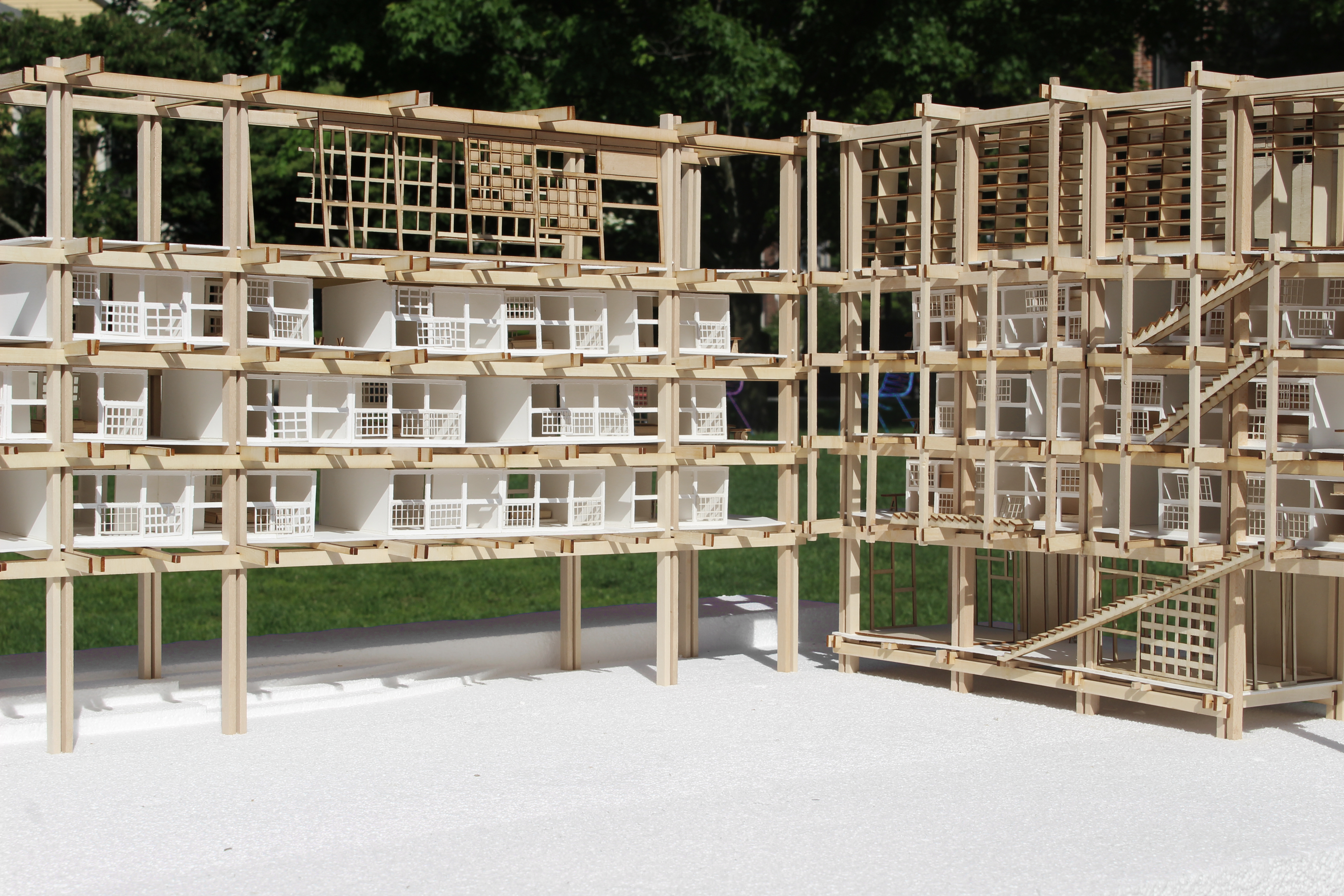

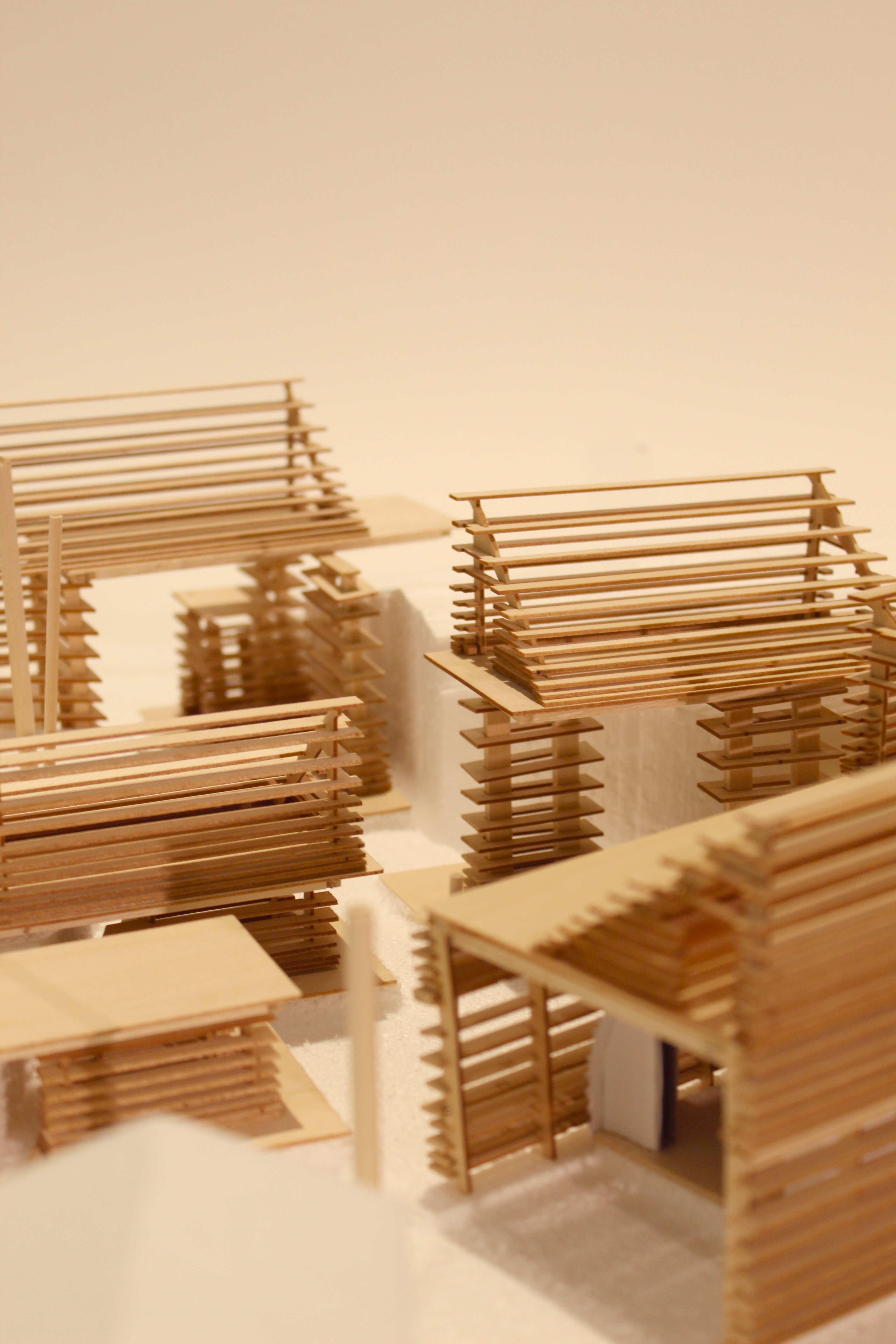

The resulting projects are diverse: a vertical kindergarten, a compact live-work building, cultural and leisure facilities, and proposals for the redevelopment of the former market site near Shimokitazawa Station.

The work presented in this publication considers Japan’s pressing demographic shifts—an aging population, a declining birth rate, and limited immigration—while offering an alternative to recent large-scale developments in Tokyo and their exclusionary consequences.

As an ensemble, they sketch a vision for how neighborhoods like Shimokitazawa might regenerate themselves through collective and collaborative action. Here, architecture becomes an important catalyst for urban change. Instead of typical large scale urban design initiatives, it is the density and the proximity of the projects that support new initiatives in conversation with the existing network and life of Shimokitazawa.