Chapter II: Principles of Spatial Order

If we appreciate anything as contemporary in the Japanese images of urban space, it is the expression of space by means of the diagrammatic plotting of symbols throughout.

Take a look, for instance, at Figure 1, a modified version of Kaiho O-Edo Ezu (“Compact Pictorial Chart of Greater Edo”), which was published in Tenpo 14 (1843). The image below is our hand drawing created by tracing over Kaiho O-Edo Ezu to clarify what it intended to communicate. Leaving the chart's streets untouched, we enlarged family crests while eliminating the texts that seemed extraneous for today’s readers.

Kaiho O-Edo Ezu (Compact Pictorial Chart of Greater Edo), published in 1843, simplified by the authors.

This illustration is composed of two elements: first, the layout of properties as defined by a network pattern of streets, and second, family crests showing the location of feudal lords’ domains along with symbols of landmark temples and shrines. The largely unaltered pattern of streets, moats, and canals allows comparison with the equivalent central part of present-day Tokyo. You would then discover the inaccuracies in this pattern.

Deviations from the actual streets, together with the plotting of symbolic marks, conversely enable us to form a more “accurate” image of the city of Edo. The arrangement of family crests gives us a good idea of the location and orientation of important landmark facilities, while cartographic distortion in the road network let us discover different degrees of importance or interest at that time in Edo. For example, the street distances in the center of the map are relatively accurate, while those toward the periphery are radically compressed. Lower levels of interest translate into a reduction of street length.

Such map distortions and informative distribution of symbols can still be seen in many tourist pamphlets and the like. Even so, such anonymously produced tourist material is bound to be a greater boon to you than the 1:50,000 scale map of the General Staff Office [the central organization of the military] that boasts high accuracy, or an urban planning map based on surveyor data. Insofar as it presents a faithful image, an abbreviated diagram conveys urban space more accurately.

Even without resorting to cubism or Riemannian metrics, the fact that expressions deemed “inaccurate” in terms of absolute distances or surveyable bearings might convey a more “accurate” image is wholly acceptable to Japanese sensibilities. When proposing an analytical image of urban space, we recognize that a distorted abstraction can better convey reality than a precision planar projection. As such, it is now important for us to evaluate and engineer the Japanese sensibility of spatial expression in a contemporary way.

The very notion of conveying a spatial image implicitly incorporates itself in the means of expression. The reality of physical urban space does not exist outside us, but arises within our consciousness at the moment of cognition, which is why the means of expressing urban space must essentially serve to convey internal images. Only by pursuing such systematic means can we allow real spatial cognition.

Urban spaces have at times reflected an image of cosmic space itself, especially in past eras when the whole of human life was thought to be governed by cosmology.

This differs considerably from today’s segmented world view in which our human existence is seen as a microcosm in relation to the greater macrocosm ascertained by modern physics (though this is really only a very recent development). Throughout most of history, the human microcosm was synonymous with the macrocosm.

The same held for establishing urban spaces. While some aspects of cities are affected by geography and the distribution of functions, cities in the Orient were often configured as extensions of the macrocosm and determined by near-magical worldviews. A syncretic merger of ritualistic Buddhism and Taoist yin-yang geomancy (onmyodo) often dictated set patterns for urban spaces [ed: in the case of Japan].

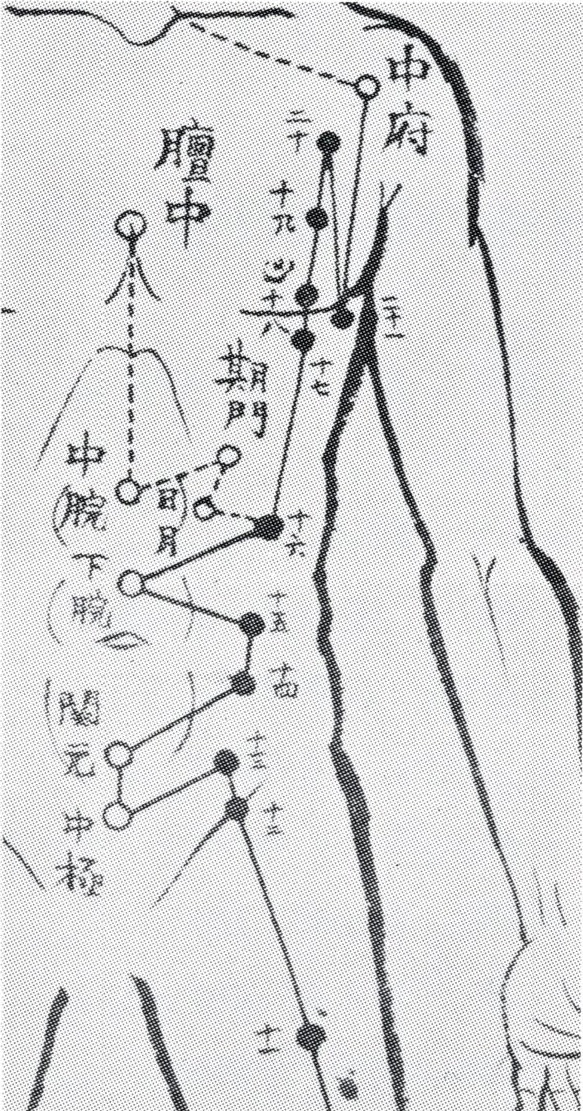

One basis for such cosmic schemes can be found in tantric mandalas. Without going into all the religious doctrine and philosophy behind them, the visual order of mandalas is of key interest. Intended as diagrammatic aids for imparting esoteric teachings, mandalas were two-dimensional representations of a pantheon of Buddhist deities as they were imagined to exist in cosmic space. The total configuration was thus identified with the macrocosm, and the act of illustrating that order within the limits of a picture plane was tantamount to creating a new cosmos. Only by merging with this cosmic order of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas did humans attain existence in an instant of union with the universe. In a word, this was a grand aesthetic of cosmogenesis [Fig. 2].

One important fact here is that in their most primitive form, mandalas were temporary constructs of colored grains of sand, ritually laid out on the ground only to be destroyed in the end. Condensed re-creations of the all-pervasive Buddha cosmos, the totality of the universe in compact form here on earth, they often depicted sacred royal palaces where the Buddhas reigned. The overlapping imagery of cosmic space, urban space, and actual persons sitting at a fixed place on the ground going through the rituals all fused together as the mandala—a macrocosm of Buddhas, each with its own meaning and frequently symbolized with stylized Siddhāṃ script (bonji, in Japanese).

Persons sitting around such sand mandalas would be looking down on cosmic space from above. Only later did they come to be painted for hanging on the walls of esoteric Buddhist temples, confronting viewers head-on, although they still presented an aerial view. This, in sum, gave rise to the Japanese image and expression of space as a distributive mandala overview.

The representation of urban space was, after all, a diagram of a distribution.

(top left) Mandala schematic: mandalas originally emulated royal palaces.

(top right) From the Three-fold Mandala of the Two Realms. The Trailokyavijaya Realm is shown in the present.

(bottom left) The Sephirothic “Tree of Life”: the structure of the cosmos is shown numerically.

(bottom right) A Kabbalah diagram of the cosmos: a macrocosmos is an image of a microcosmos.

By way of contrast, another spatial schematic can be found in the mystical Jewish Kabbalah, wherein the universe is composed of twenty-two Hebrew letters and ten numerals. By manipulating these letters and numbers, Kabbalists believed they could discern the inner workings of the world and come to an understanding of God via speculative reasoning. This ten-digit Sephirothic “Tree of Life” representation of the cosmos is nothing like a distributive mandala, but rather shows a conceptual structure based on relational principles. The ten lettered nodes (sephirot) are said to constitute cosmic principles as well as to underwrite human existence. Thus, it is not a pictorial image to be viewed, but a catalytic means for speculative understanding—a symbolic structure of principles, a systematized theoretical expression.

The Kabbalists depicted the macrocosm on the microcosmic scale of humans themselves. Their cosmos appears as an analytic diagram of a human figure labeled with God’s names. Not an array of diverse persons and material objects, but a singular cosmic structure composed of various elements, all abstracted as prima materia for speculative reasoning.

While the Kabbalah is also an esoteric art, its analytic method served to inspire alchemists and also led to the Renaissance discovery of optical perspective, which is a purely structural take on space, not a distributional notion as in mandalas.

[In Japanese history] aerial views were commonly used for depicting city panoramas. The Machida family’s heirloom folding screen of Rakuchu Rakugai-zu (“Scenes in and around Kyoto”) [Fig. 3]. painted over twenty-five years from 1521, presents an aerial composite of important sites in Kyoto throughout the year and the seasonal festivities of the period. The entire surface is dotted with a panoramic compendium of different scenes.

Of course, aerial-view pictorial techniques existed in the West as well. A 1562 engraving by Marcus Gheeraerts [Fig. 4] shows the center of a classic mediaeval European city as seen from above. The difference between the two aerial views should be obvious. In the Kyoto screen, areas of clouds and haze (un’en) cover a good portion of the overall surface, revealing only those vignetted elements deemed noteworthy in the city as a way of distribution or disposition. The engraving, on the other hand, employs what we now call isometric projection to show a full continuum of all elements in meticulous clarity. The former consciously abbreviates the cityscape with subjective intent, while the latter tries for logical objective accuracy. Although both employ an overhead view, the quality of the space represented there is fundamentally different in character.

Kano Eitoku, Folding Screen of Rakuchu Rakugai-zu (“Scenes in and around Kyoto”), the Uesugi version (a partial view), 16th century. Property of Yonezawa City Uesugi Museum.

Marcus Gheeraerts, City Plan of Bruges (partial), 1562.

As art historian Hisatoyo Ishida has pointed out, the pair of Machida screens are composed so that all lines converge on a single viewing spot that corresponds to the top of the seven-story pagoda that once stood at the Shokokuji temple in central Kyoto, thus taking in a simulated “Cinerama” sweep of the city all around. The isometric rendering is nothing so dramatic. There is no variation in the density of spatial expression from one area to another; all areas are filled in via the exact same cubic grid projection. A methodical, even clinical, eye permeates the entire picture plane uniformly with no subjective emphasis on any one part, clearly exemplifying a belief that the sum total of detail equates accuracy. As such, the urban space appears to have been placed outside of subjective perception.

So what, then, is the secret to the dramatic grasp of the city in the Kyoto screen? One particularly effective technique is the “clouds and haze” tradition, which makes for a surprising artificial manipulation of focus, rendering the external (objective presence) internal (imagined presence). Another is the compositional aesthetic that distributes symbolic elements throughout in a mandala-like overview. The screens are a grand summing up of these methods.

Mandalas, being macrocosmic layouts of image elements, cannot be criticized as “unrealistic.” And yet the Kyoto screens, for all their mandala diffusion, purport to depict the actual city. However realistic the individual elements—details of buildings or festivities—they are cut off from one another and suspended between obscuring clouds. Where the actual city would be a single continuum of amassed elements as in the isometric engraving, here the clouds create a selective discontinuity that makes spatial relations entirely relative.

Distributive layouts consist of elements in relative spatial disarray. From mandalas to Kyoto screens, there is constant sense of relativized symbolic space. Inasmuch as the structure of urban space as we perceive it is by no means just an aggregate of realistic representations, but rather expands upon the rhythm of our impressions moving through the city, a discontinuous arrangement of close-up symbolic elements in relative to each other can deliver a true-to-life image of urban space effectively—in fact, that would be the only way to represent urban space accurately.

We can analyze such discontinuous relativized spaces from a contemporary viewpoint by seeing what specific methods are applied to which elements to give them symbolic meanings. We may also note the relative distance, the time lapse between them, the orientation, or the order of importance in certain formats, which add a further dimension of meaning to the overall space. Signifiers such as modulations of light and dark, breadth, axis of view, angle of incline, and other compositional components all factor into the picture. These many processes contribute to the abstraction and visualization of urban space into a more accurate sensible expression. As case studies show [ed.: see chapter V], we should retain clearer spatial memories of symbol-strewn layouts.

The invention of perspective accentuated the image of Renaissance European star-shaped bastion fortresses and further developed multifocal expressions with the rise of Baroque-era radiant-plan cities—so goes the prevailing theory [Fig. 5].

While ideas of Western perspective have occasionally impinged upon Japanese spatial expressions, they ultimately met with resistance here because space was never taken as a physical quantum to be analyzed, but rather as an intervening “ma” positioned relative to various other elements [relata].

In actual fact, the most typical formation of Japanese urban space is what we call the classical esoteric (tantric) Buddhist type, whereby we experience space tracing dot by dot, formulating one linear trajectory of memory. Witness Hiroshige’s Fifty-Three Stations on the Tokaido Road or the pilgrimage trail to eighty-eight temples in Shikoku. Space comes about experientially by people entering and moving around in it.

It should go without saying that when our image of a space is so intrinsically connected to moving viewpoints, fixed-point perspectives cannot give a sense of that experiential space as a whole. The basic principle of perspective consists in establishing a fictitious “vanishing point” focus to which sight lines from all elements are drawn together, providing a linear scale for expressing distance by proportional reductions in size. Conversely, it also serves to highlight a singular human presence within the space as the source of those visual lines. In that sense, Western perspective is the very reification of individualist spatial feeling.

A Baroque city viewed in perspective.

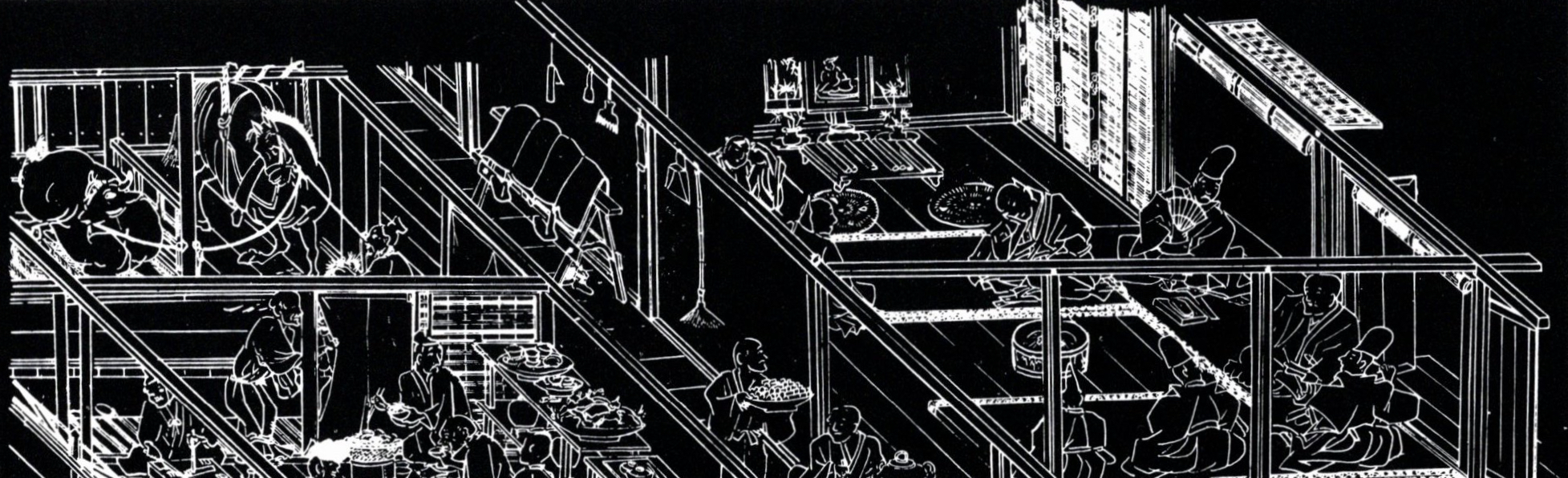

Fukinuki yatai house interiors depicted with roofs removed in Fujiwara Takamasa and Takaaki's Boki-ekotoba (a picture scroll in memory of the Buddhist saint Kakunyo), 1351.

However, such perspective cannot happen within spatial images that build up via ever-moving viewpoints and remembered experiences. Movement necessitates doing away with such a fixed and reductive scheme of expression. Perhaps it made sense in early-modern European cities with their radiating streets, but in the sprawling conurbation of Edo with the Edo Castle (present-day Imperial Palace) at the center, streets almost formed a whirlpool, which suggests the general view of space as no more than a linear twill weave.

Spatial awareness via ever-moving viewpoints led more naturally, in the case of painted handscrolls, not to panoramas of contiguous scenes but to sequences of disparate scenes. The viewpoint wanders as if floating over each independent scene. It is unthinkable that the viewpoint would halt completely for even an instant. And since the eye is always in motion, it is impossible to maintain a fixed focus on what is depicted. Images before and after tend to overlap, subjects stay independent with no continuity, and yet compositionally there has to be some internal sense of continuation. One method of dealing with this [paradox] was to present a mandala-like panoply of relata, not distributed over a planar surface, but in linear succession. Or else, as in the Scenes in and around Kyoto screens, by arraying them in extremely abbreviated form vignetted by clouds and haze, thereby eliminating any unnatural [literalism.]

We may find similar examples in the reverse focus and multiple focus of scroll-painting depictions of house interiors with the roofs removed (fukinuki yatai) [Fig. 6] or the [graphic] combination of diverse elements in ukiyo-e print compositions. While not unlike the non-perspective discoveries of the Cubists, instead of their analytical approach, these Japanese pictorial conventions create something like spatial sense of “ma” generated via moving viewpoints, based in the sequential experience of space. Not an analytic vision, but a compound-imagery grasp of space generated sequentially in time.

We have learned through our survey of these Japanese techniques of expressing urban space that they are about representing space with symbols and that the sequential experience of such symbols evokes a linear composite of images.

In contrast to the European technique of rationally analyzing the city as exactingly as possible in order to render a precise realistic expression of the actual physical space, the Japanese way is an unrealistic or virtual image that appears as an internalized expression of space. Rather than trying to capture the actual space, this approach of ruminating the image into abstract symbols is taking on greater importance in analyzing contemporary urban space.

The city will be a composite of diverse component sources and will surely become ever more profoundly complex. Adhering to mere quantifiables cannot take in all that goes on within such space as it occurs. We must translate it via the symbolic manipulation of images perceived within the complexity. In order to simultaneously communicate both the material forms and activities of urban space, we must establish a systematic means of symbolic manipulation. The image of urban space will undergo ever more change in the contemporary city; not in actuality but in virtual images, not the material forms but illusions, soon the density of signifiers will no doubt increase exponentially. As urban space becomes nothing more than a setting for such signification, it will probably end up being a kind of atmospheric environment of signs.

We may find such imagery of spatial representation within Japanese urban space. By grasping the mechanism and effect of the techniques that used to be sensible and intuitive, we should be able to turn it to a critical method of conceptually imaging the contemporary city. Just looking at techniques of representation, Japanese urban space seems to suggest many issues linked to contemporary urban space.

The translation of the parts of Nihon no toshi-kukan [Japanese Urban Space] was made possible by courtesy of the publisher. Nihon no toshi-kukan was written by Toshi-dezain kenkyutai [Research Group for Urban Design], edited and published by Shokokusha Publishing Co., Ltd. in 1968.