Chapter II: Principles of Spatial Order

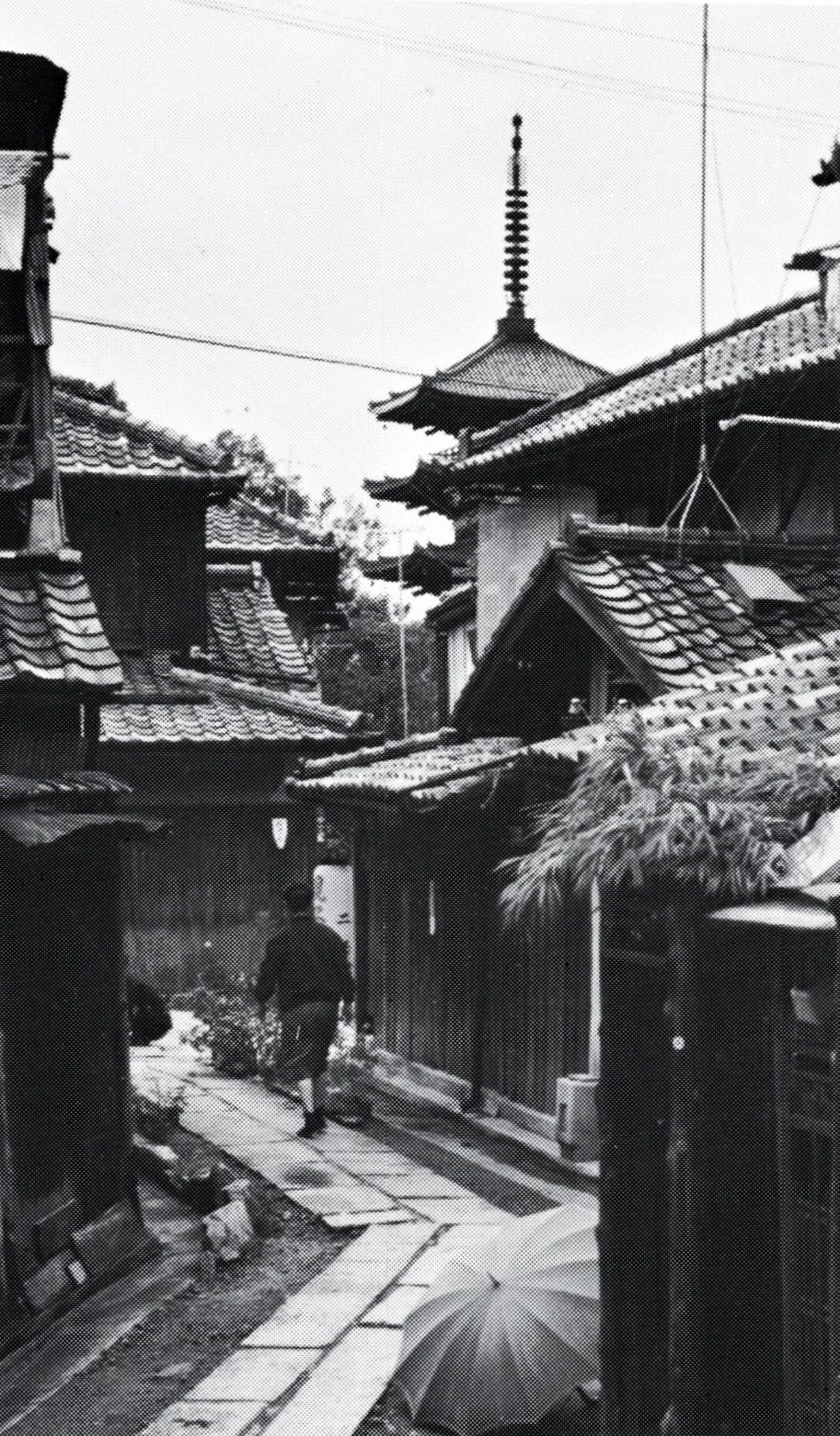

This scheme of spatial composition involves arranging elements so that they cannot be seen in their entirety from a stationary vantage point; only by moving around can we view all of these elements as laid out. The Yasaka and Kiyomizu pagodas in Kyoto are good examples of this, as they are not visible from every point along the street; they dodge into and out of view enjoyably as one walks along. Thus, despite their height, these towers cannot fully serve as landmarks.

While this miegakure technique no doubt derives in part from the value the Japanese place on not revealing everything at once, it also serves to make small spaces appear bigger and to stimulate the aesthetic imagination, intentionally heightening the drama and beauty of unexpected changes.

There are three general ways to go about achieving this: sawari (obstructing), haichi (positioning), and katachi (shaping) elements. An example of the first method might be to plant trees in front of a building, as with a monastery half-hidden by a row of pines. Or by, when laying out a garden, positioning a tree before a stone lantern or waterfall so that the light seen through the leaves suggests the glimmer of distant fishing boat torches (isaribi) or lets viewers imagine a much bigger cascade.

As an example of the second method, the fifteen rocks of the famous rock garden of the Ryoanji temple in Kyoto are arranged so that, no matter where we sit, one rock is always hidden from view. The Yasaka and Kiyomizu pagodas also pertain to this category, as do most Japanese castle towers when viewed from the towns immediately below.

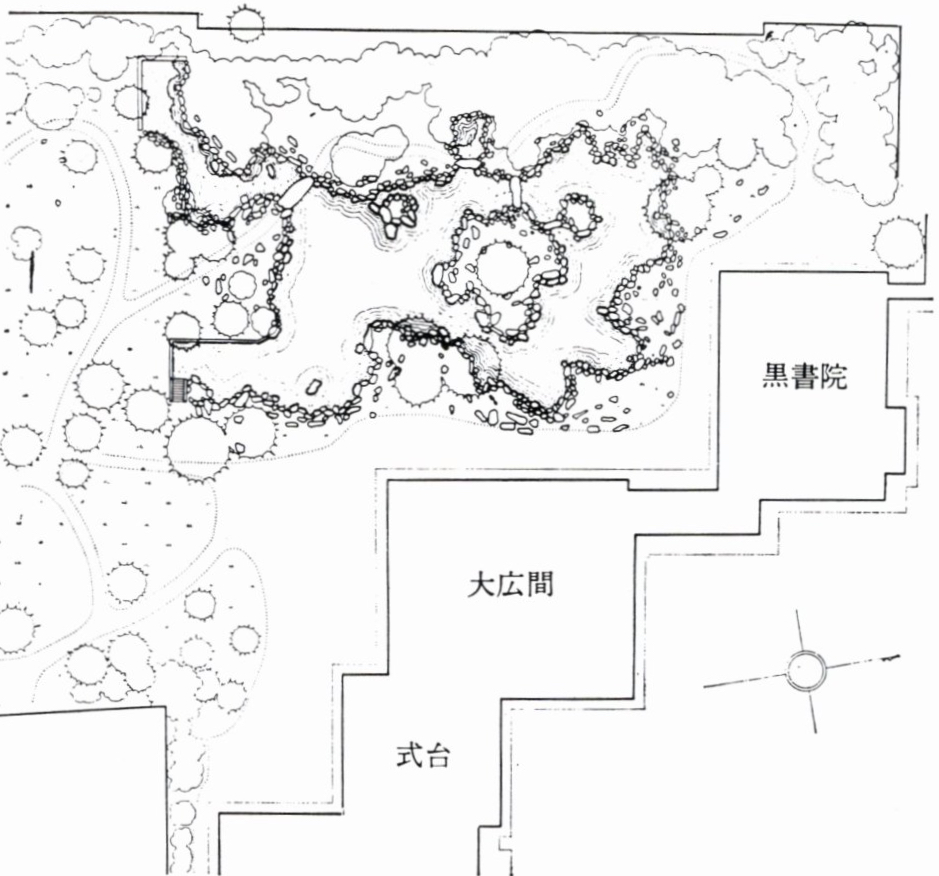

The most obvious examples of the third method can be found in the classic multi-lobed ponds of Japanese gardens, whose shapes roughly resemble the character shin (心heart). The entire pond cannot be viewed from any point in the garden, which gives the impression the pond is bigger that it actually is.

The garden in the Heian Jingu shrine, Kyoto.

A pine tree planted in a garden as a measure of nejime (a method of planting trees or grass at the base of a garden stone or stone lantern for scenic beauty, communication with the ground, modification of the base, and/or protection of the ground surface).

A character 心 shin (heart)-shaped pond in Nijo Castle, Kyoto.

The Kintaikyo bridge, Iwakuni.

A corridor around the Itsukushima Jinja shrine, Hiroshima.

The Yasaka pagoda, Kyoto.

The translation of the parts of Nihon no toshi-kukan [Japanese Urban Space] was made possible by courtesy of the publisher. Nihon no toshi-kukan was written by Toshi-dezain kenkyutai [Research Group for Urban Design], edited and published by Shokokusha Publishing Co., Ltd. in 1968.