Chapter II: Principles of Spatial Order

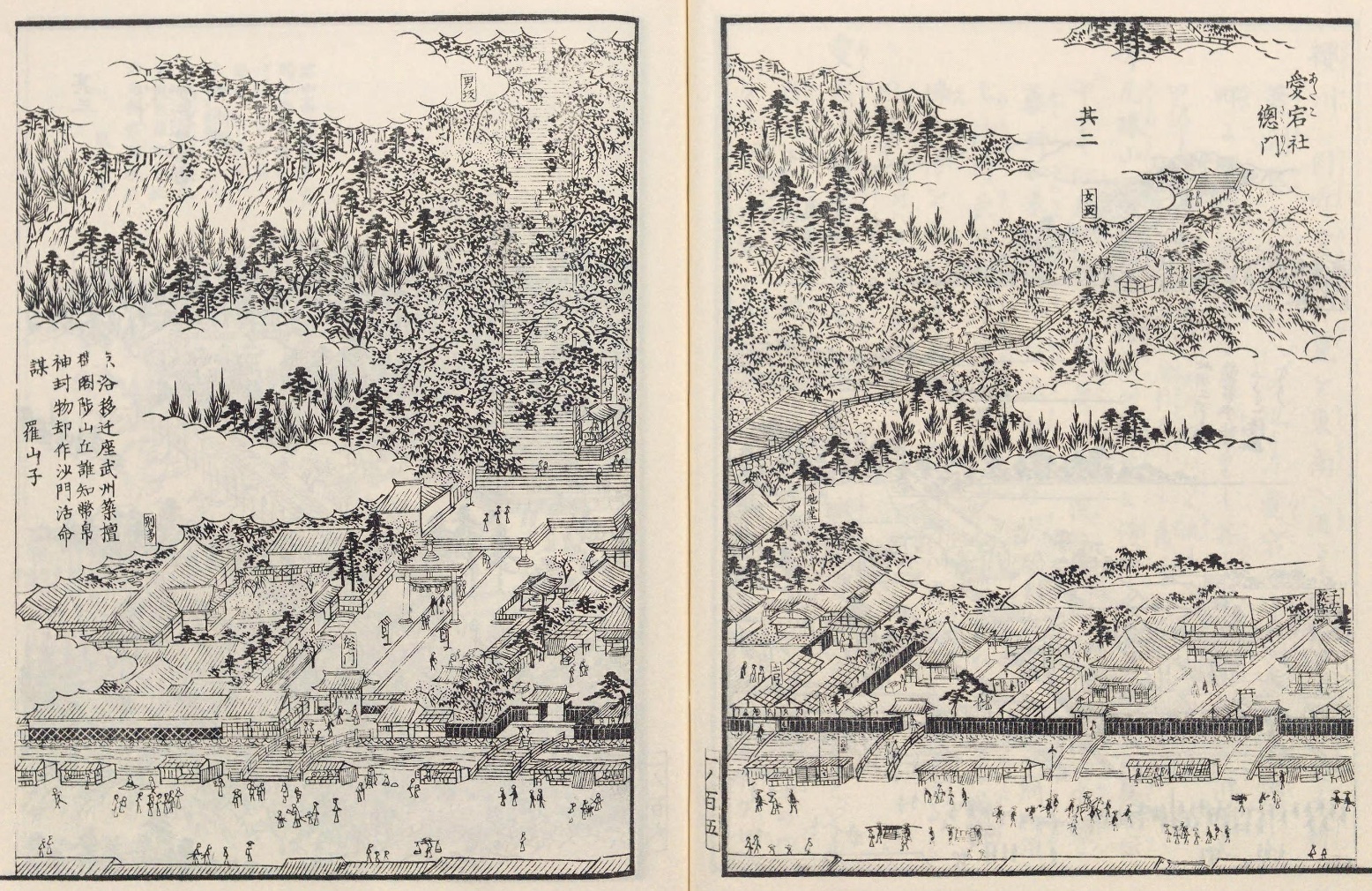

Approaches to Shinto shrines on elevated sites generally take two paths. The Atago Shrine in Edo (modern-day Tokyo) overlooked the Shinagawa waterfront and most of the city of Edo, as well as offering a view of the hills of the Boso Peninsula across the bay. The main approach (omote-sando) to the shrine is comprised of an impossibly steep 85 stone steps, commonly known as the otoko-zaka (“men’s incline”). To the right of the stone steps rises a more gradual 108-step approach (waki-sando) called the onna-zaka, or “women’s incline.”

Although the principal difference between the two sets of steps is the slope, the variants made for distinct views and differently textured experiences. Shrine-goers would typically arrive via the otoko-zaka and exit by the onna-zaka, and at crowded festival times the twin paths effectively provided smooth one-way passages for worshippers.

The dual approach system became commonplace in shrines throughout Japan from the 17th century on, as [codified] Shinto gained popularity, especially among women.

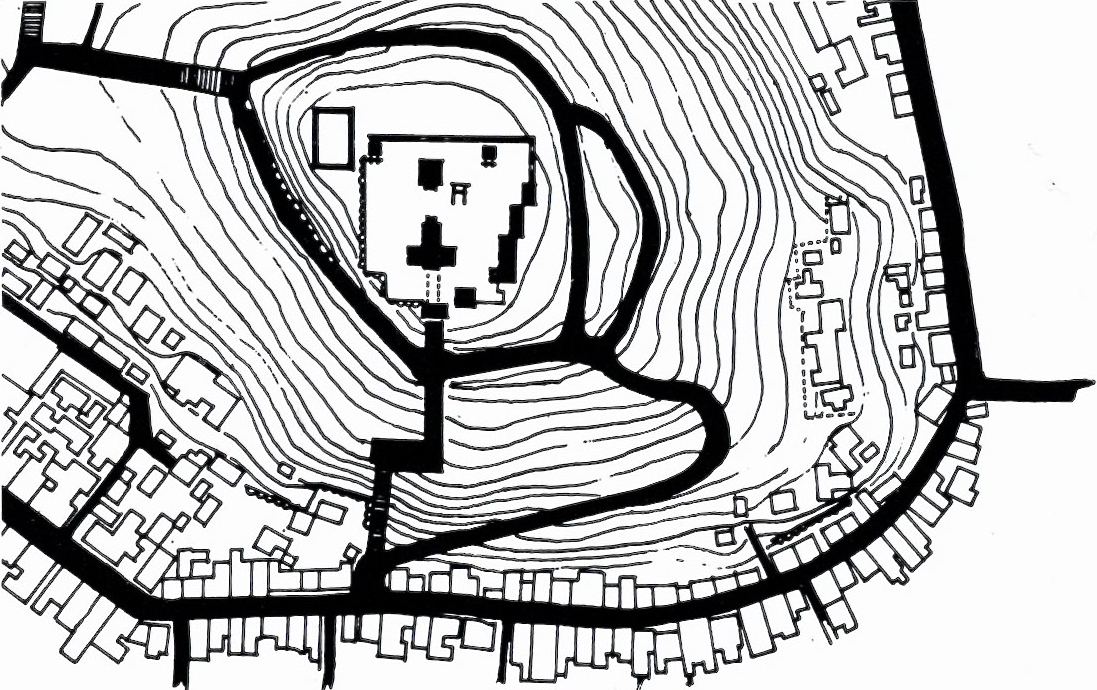

Today, in Tokyo alone, we may find this pattern at the Yushima Tenjin shrine, Ichigaya Hachiman shrine, and Iigura Hachiman shrine. The gradual onna-zaka of the latter two shrines have since been converted to automobile driveways, perhaps indicating that the male/female or class divisions of feudal times have now been supplanted by human/machine hierarchies.

The steep and gentle stairways of the Atago Jinja shrine.

The Atago shrine depicted in Edo meisho zue (a pictorial book on the history and specialties of Edo and its suburbs, published in 1834 and 1836).

The Ichigaya Hachimangu shrine, Edo.

The steep and gentle stairways of the Achi Jinja shrine, Kurashiki.

The translation of the parts of Nihon no toshi-kukan [Japanese Urban Space] was made possible by courtesy of the publisher. Nihon no toshi-kukan was written by Toshi-dezain kenkyutai [Research Group for Urban Design], edited and published by Shokokusha Publishing Co., Ltd. in 1968.