Portraits of Landscapes—Part 1

The benefits of biodiversity to human society, traditionally referred to as the blessings of nature, can also be described as “ecosystem services.” The idea behind this expression is to leverage the word “service,” in its economic sense, so as to situate ecosystems within an explicitly anthropocentric worldview. At first glance, this may seem like a brazen declaration of anthropocentric egoism, but this language has the power of recasting the baffling concept of ecosystems in concrete terms, as negotiating parties with interests of their own. In turn, this power emboldens a viewpoint that sheds light on how diverse and profound ecosystems really are.

What made a term like “service” pop into my head was a sense that the viewpoint it engenders may in fact have been what our research was missing. Whether a space is overtly designed or lacks design, is made by human beings or is a natural setting, like the shade under a tree, all spaces can be viewed through the lens of service, or how they benefit people.

Even the shade of a tree, created incidentally by nature, can be evaluated in terms of how it benefits society. In so doing, an abstract concept like “shaded space under a tree” transforms from a kind of symbol into an aggregate of concrete features constituting a space. Consider this photograph of small boats on a river. It may look like no more than an assortment of evenly spaced boats, tooling around the water, but if conceived of as a skillful utilization of the buoyancy provided by the water, as a service, the abstract concept of water takes on concrete implications, prompting consideration of other uses for the buoyancy.

What we can see in “Floating,” the title of the unit of photographs containing the boat photo, is how floating objects create an equilibrium between attraction and repulsion. Whether it’s shrinegoers strolling up a shaded path, or hotel guests relaxing in a serene hotel lobby, we can observe a delicate maintenance of even spacing, promoted by the curious imbalance and ample breadth of the space itself, as with boats on the water. The general effect very much resembles the buoyancy provided, as a service, by the river.

Thus, the concept of service can prompt our imagination to consider things we usually overlook. This leads to questions like how people contribute to a space, what value the contributed service has, whether the means of delivery is appropriate, and whether better means of delivery are available.

The framing effects of a variety of elements that offer some form of service, as found in a snapshot. 1. Neatly displayed goods add a context. 2. The window frame gives the image a tightening effect. 3. The tree in planter with green foliage provides some shade. 4. Stylish electric decorations add liveliness. 5. Birch branches suggestive of the highlands lend the scene a refreshing mood. 6. The handmade signage is welcoming. 7. The potted tree with Western foliage gives a brilliant look. 8. The large bench offers a moment of rest. 9. A person surrounded by all these elements takes a mouthful of a tasty sweet.

A proper combination of features for workers to perform tasks, as found in a snapshot. 1. The environment protects workers from wind and rain. 2. The outdoor air-conditioning unit shows that this is a semi-outdoor space. 3. A level floor surface enables office work. 4. Space to park a truck. 5. High ceilings with good visibility. 6. Plenty of room where things can be left cluttered. 7. Brightness. 8. Electricity freely available for fans, etc. 9. A worker finds comfort in a spacious and functional space.

Seen this way, the spaces that attract us so much that we want to stop and stay there can be understood as offering a rich variety of services. Moreover, we can also understand the delivery of services, and the receipt of services, as being demonstrably effective. In our conversations, my students readily personified the different spaces made by trees or man-made objects, calling the trees “comforting” or a group of tents “impressive,” which I think ultimately indicates a shared, unconscious recognition of the services provided by these spaces.

With this perspective in mind, it can be said that what grants lived places their appeal is that the spatial services they provide have been thoroughly refined over time—maximized through the development, years in the making, of optimal methods for recognizing and capturing the geographic, atmospheric, ecological, and artificial benefits afforded. This makes these soothing atmospheres, which have a sense of density and completeness, like being at the center of the world, a source of insight.

This begs the question of who should initiate this process of refinement, and when, but it is best to let the possibilities branch off in multiple directions. One way is through something like a pattern language, formed collectively and with an eye toward gradual progress, but the experiment could take place in a single line drawn by an architect. Moreover, by dint of the fact that the planner can only contribute an abstract version of the space, or in other words provide a limited service, the rest is left to the imagination of the users. In any case, I think what matters most is finding language that allows for these various elements and services to be viewed objectively, in technical terms, through a single frame of reference.

What we discovered, after months of searching, was a throughline between impromptu structures, the imprints of objects, and the traces of activity that allowed for all these spaces to retain their idiosyncratic purposes and meanings, while accounting for the ways that people naturally gravitate to soothing environments. These physical spaces are packed with all the factors necessary for survival, in the way a healthy forest supports the life-forms living there.

These magnanimous and fecund spaces vary widely, from examples of human handiwork to the felicitous creations of the natural environment, but when viewed through the same frame of reference, one readily detects the presence of a number of services geared foremost toward the climate and the ecosystem. People congregate in areas rich in services and build structures for reaping their benefits. This undeniable fact offers a clue to answering questions like “what are we making” and “why are we making it.”

Incidentally, though pattern languages might extrapolate on methods for accessing a variety of services, like sunlight, the effort to unlock the sources of an “unnamable quality,” or the force behind what we might call lived places, prioritizes the systematic extraction of universal patterns in such a way that overshadows what inspires that quality in the first place. Motivated in part by a dissatisfaction with this kind of approach, we sought to direct attention to the “expressiveness” of spaces, even as we derived countless patterns from the scenes. The charming places we encounter in everyday life support a dynamic relationship between people and services, while the spaces they create have a certain expressiveness. Our endeavor was not to abstract patterns from the landscape, but to extract the expressiveness they have to offer. Perhaps the word expressiveness, so bound to animal life, sounds like a stretch. But when we find ourselves faced with a comforting landscape, we have a way of reading what we see as if it were a welcoming expression.

Whereas expressiveness manifests in animals through the ways the face and body show emotions, the expressiveness of spaces is felt when a space, as a web of visual information, generates a kind of traction that tugs at our physical experience and memories, thanks to a prevailing calmness or a tidy organization. Looking through such a large volume of photographs, one begins to detect the expressiveness of the spatial services each place provides. This expressiveness is probably the very thing that provoked us to take each one of the pictures in the first place.

For those of us unconsciously enamored with the smile cast by spaces, these units of photographs are veritable portraits of landscape. Through continued observation of these expressive spaces, which sometimes grin and at other times play dumb, the imagination starts to grasp the circumstances that give rise to this expressiveness. This way of seeing the world points to the headwaters of creation, which flow through any built environment that fosters comfort and activity. Hence our decision to adopt a format in which spatial structures revealed by the photographic units are condensed into a simple commentary, rather than expressed schematically, giving the photographs space to speak for themselves.

In retrospect, it was the process of looking through a huge number of photographs that alerted us to their expressiveness. Hiding behind every expression, diverse and potent lived experiences are waiting to be found. These translate into a variety of services. In establishing a clear view to the origins of service, we can sustain that eureka moment when the photographs reveal their patterns. By playing with options, we can harness our imaginations and create new patterns for utilizing the wealth of services available, arriving at a navigable circuit of ideas. Ultimately, this perspective is the greatest takeaway of our research.

• • •

Turning an analytical lens on the bench that I found in the disaster area, with the benefit of hindsight, I can see that the landscape provides a view, while the branches provide a comfortable place to rest, reinforced by the two chairs. Meanwhile, the devastation of the world stretching below emphasizes the tranquility of this little space, almost excessively. While each of these spaces, from a compositional standpoint, is no more than an aggregate of services provided by the landscape, trees, people, and circumstances that form them, they take on special meaning when abnormal circumstances, like the aftermath of an earthquake, reorder them in novel ways, creating something far greater than the sum of the parts. Within this context, I cannot help but feel a force that can only be described as benevolent, generated by the expressiveness of the space. Finding benevolence, in any scene, is not a common thing. Sensing something of a miracle at play, we tried to capture it on camera. That said, we cannot conceive of these sacred spaces as purely technological propositions, nor should we even try.

All photographs courtesy of © Kumiko Inui, Inui Architects, and the Inui Lab at Tokyo University of the Arts.

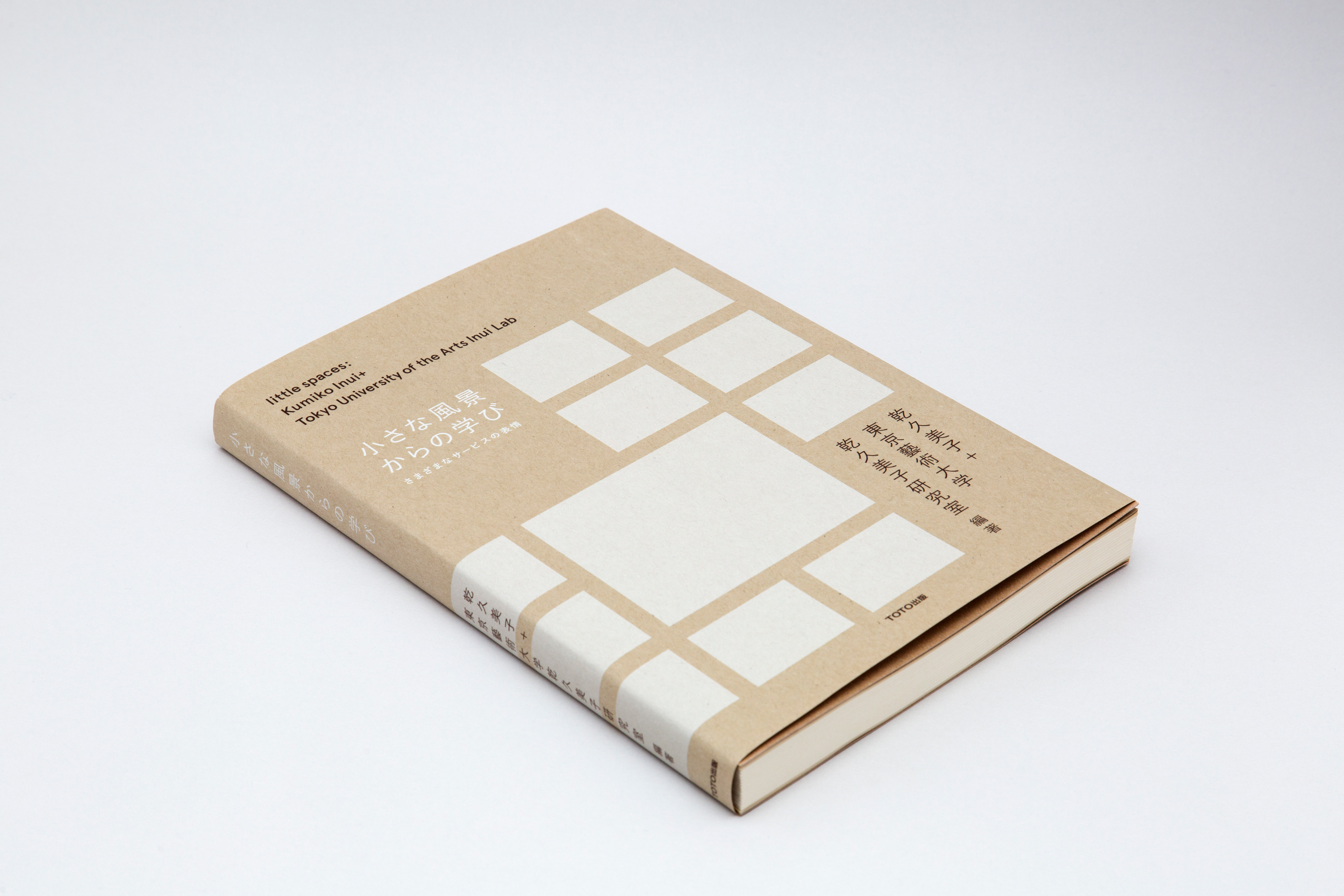

This essay and the associated research stories were originally published in the book little spaces (TOTO Publishing, 2014) by Kumiko Inui and the Inui Lab at Tokyo University of the Arts. Their publication on JapanStory.org was made possible by the courtesy of the authors and the publisher.